How Women Broke Into the Male-Dominated World of Cartoons and Illustrations

A new exhibition at the Library of Congress highlights female artists and their contributions to comic strips, magazine covers and political cartoons

:focal(403x186:404x187)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/ae/78aeb86c-9af8-4d41-93b8-304da30c3de0/dale-messick.jpg)

Early in her career, Dalia Messick, a cartoonist struggling to get her work published, got a couple pieces of advice from the head of the Chicago Tribune-New York News Syndicate’s secretary. First, change your character’s profession, she said. And secondly, change your name.

Messick obliged, recasting her bandit protagonist as a roving journalist and adopting the pseudonym "Dale." Her strip, “Brenda Starr, Reporter,” became nationally syndicated by the 1940s. A decade later, it was in over 250 papers. Readers delighted in the globe-trotting adventures and romances of Brenda, the redheaded career woman.

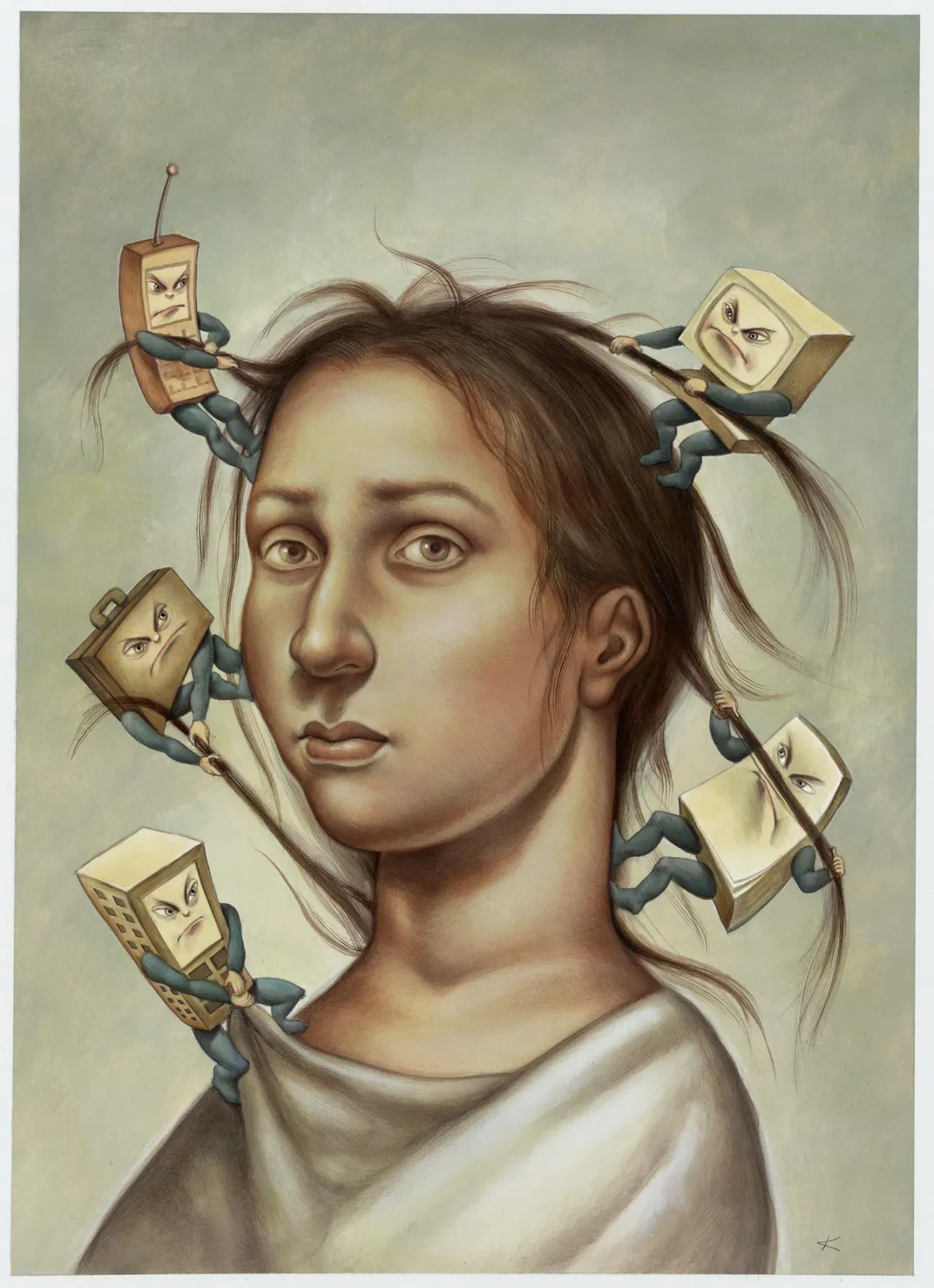

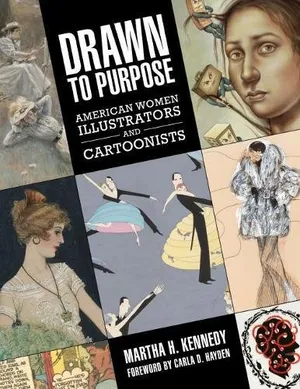

Messick’s story is just one example of the overt sexism faced by female artists. A new exhibition at the Library of Congress, “Drawn to Purpose: American Women Illustrators and Cartoonists,” is dedicated to exploring the lesser-known, centuries-spanning contributions of female artists who broke into these male-dominated fields.

Martha Kennedy, curator of popular and applied graphic arts at the Library of Congress, centered the exhibit around two themes: She wanted to explore “how imagery of women and gender relations has changed over time” and “how broadening of subject matter happens over time and in different art forms.” Ultimately, the goal, Kennedy says, is to “foster a sense of shared history among female artists, inspire younger generations entering these specialties and spur further research in the library’s collections.”

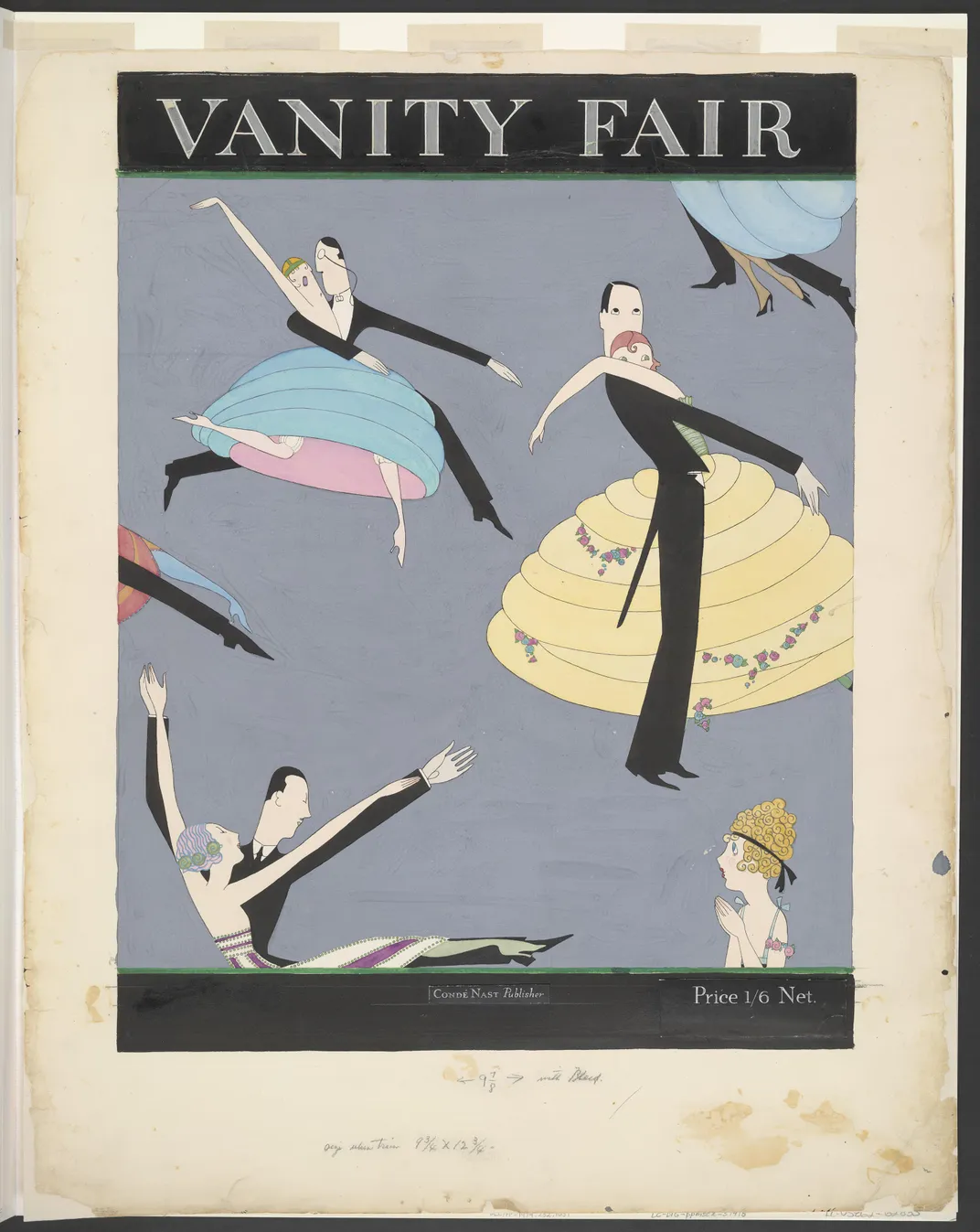

The exhibit features nearly 70 pieces from in an impressive array of 43 artists, with work from the 19th century to today. The artwork ranges from Alice Barber Stephens' Impressionist-influenced illustrations to Anne Harriet Fish’s elegant, fine-line drawings that graced more than 30 Vanity Fair covers to Roz Chast’s frenzied and funny cartoons in The New Yorker. Even so, Kennedy saw she had more ground to cover, so she wrote a companion book (out in March) and curated a second rotation of the show, with an entirely different lineup of artists, to replace the current one in mid-May. “There are a lot of women who did really interesting, innovative work who have been overlooked and are worthy of further study,” Kennedy says.

The earliest examples are those female artists from the “Golden Age of Illustration”—the years between 1890 and 1930 that paralleled the turn-of-the-century renaissance in publishing. As magazine, newspaper and book printing flourished, many women, who were trained in fine arts (although prohibited from drawing the male nude), built careers out of illustrating children’s books. Jessie Willcox Smith’s illustrations for Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies, for example, are among her most admired work. Many of the women also drew for magazines, including Harper's, McClure’s and Scribner’s. Coinciding with the emergence of the “New Woman,” a feminist ideal that took root in the late 19th century, several artists drew scenes from outside the domestic sphere and examined changing conventions of the era. In Jessie Gillespie’s Panta=loons (published in the Evening Sunday Star in 1914), Kennedy explains, “we can see a strong shift from a late 19th century scene marked by strong social formality to an early 20th century set of vignettes that give humorous takes on fashion trends and clearly display greatly decreased formality between women and men in plausible, everyday scenarios.”

Early on, women interested in drawing cartoons and comics were often limited to certain subjects. “Those able to develop successful strips were restricted to cute children and animals,” says Kennedy. There was Grace Drayton, who created the Campbell Soup kids, for instance, and Marjorie Henderson Buell, who created Little Lulu. Rose O’Neill, an illustrator for Puck magazine, became one of the earliest successful female cartoonists when she first introduced her Kewpies in Ladies’ Home Journal in 1909. Within a few years, she created dolls based on the characters, which were so wildly popular that she became wealthy and well-known.

When Messick started drawing Brenda Starr in 1940, the comic strip marked a significant shift in subject matter. As “Dale,” Messick was able to tap into a genre of cartoons that was mostly restricted to male artists. “Featuring a worthy female counterpart to male heroes in adventure strips, Brenda Starr marked a milestone among strips by women,” Kennedy writes.

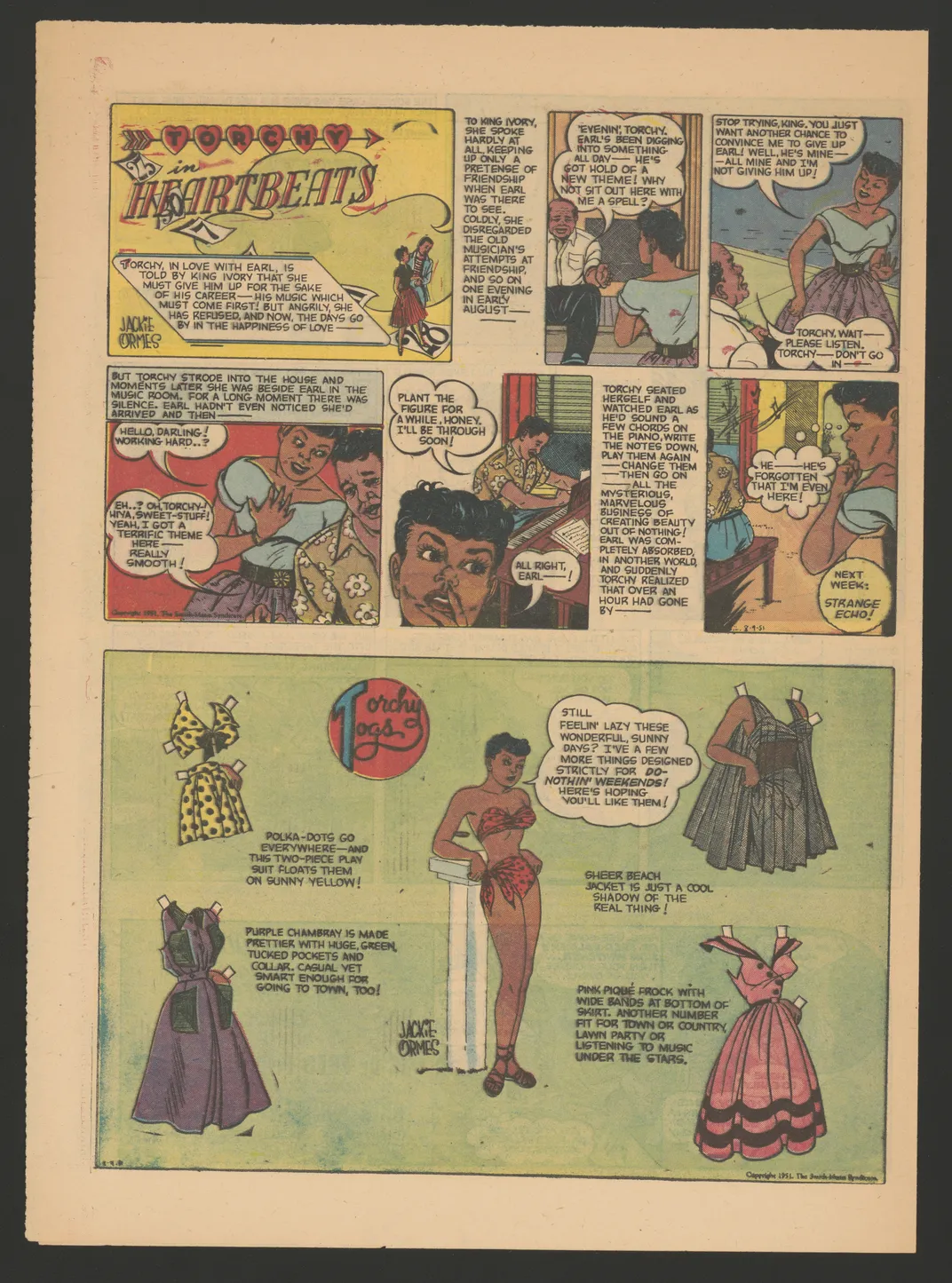

One precursor to Starr was Jackie Ormes’ “Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem,” which followed a smart and rebellious young black woman moving from the South to the North. It ran for a couple years in the late 1930s in African American newspapers; the character later returned in the 1950s' “Torchy in Heartbeats,” which is on display in the exhibit. Barbara Brandon-Croft, who was the first black woman to create a nationally syndicated strip, “Where I’m Coming From,” told NPR that Ormes’ work was groundbreaking: Her “characters and stories were real — at a time when blacks were typically portrayed in a derogatory fashion.”

The 1970s and 1980s marked yet another a shift in subject matter. Moving beyond Brenda Starr’s outlandish escapades, many female artists began to source material from their lives and those of people they knew. Lynda Barry’s One! Hundred! Demons! is a graphic novel that draws on some of her personal experiences in a style she termed “autobiofictionalography.” Alison Bechdel depicted lesbian relationships in her long-running strip “Dykes to Watch Out For” and drew on her difficult childhood in two graphic memoirs, Fun Home and Are You My Mother? With this new generation of comic artists, there’s a movement towards embracing the personal narrative.

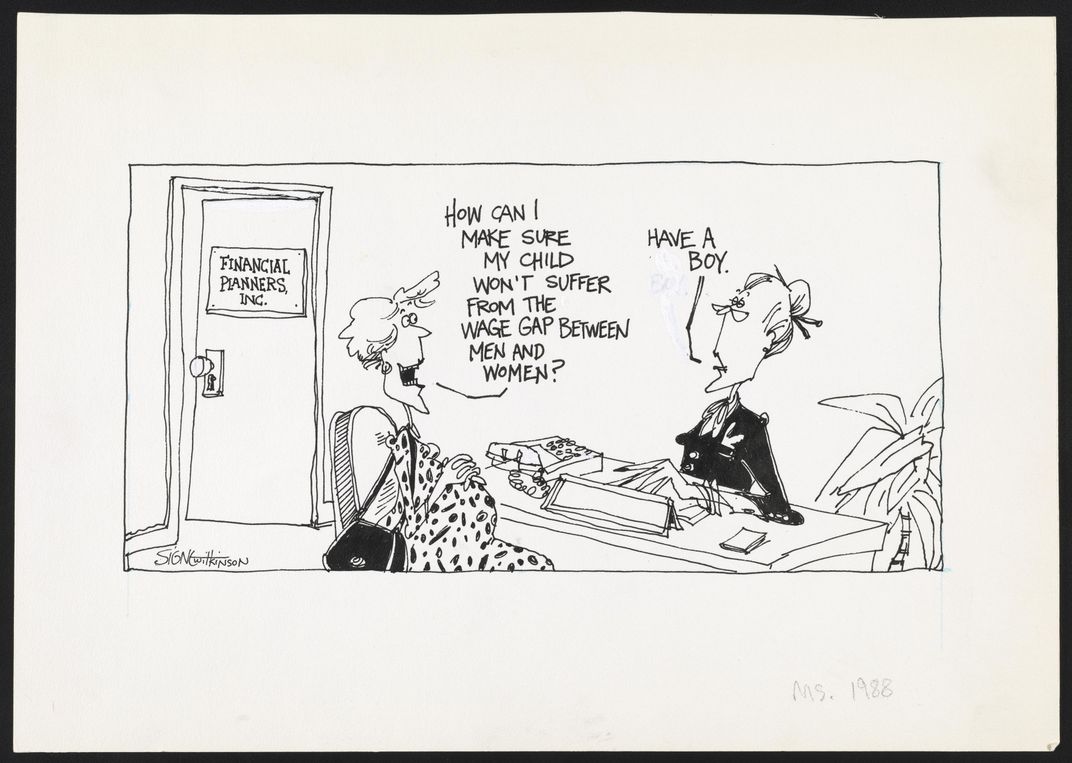

The exhibit also showcases magazine covers and editorial illustrations, as well as political cartooning, a notoriously difficult genre for women to break into. One of the earlier women to do so was Anne Mergen, who signed her work with just her last name. When she started at the Miami Daily News in 1933, she was the only female editorial cartoonist in the United States, and she carried that distinction until her retirement in 1956. Decades later, in 1992, Signe Wilkinson became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning. While contemporaries Jen Sorensen and Ann Telnaes are relatively well-known today, female political cartoonists remain a minority.

The artists featured in the exhibit span over a century of work, draw in dramatically different styles, and cover a variety of subjects, but Kennedy says, they all share immense “talent and persistence.” Pursuing art as a profession is already an unrelenting effort, she explains, but even more so for female illustrators and cartoonists who fought, and continue to fight, to break into a predominantly male career.

Female artists in these fields have historically banded together. In 1897, Philadelphia-based illustrator Alice Barber Stephens joined painter and engraver Emily Sartain to found a female artist organization called The Plastic Club, “to bring together experienced, successful artists and younger artists who were just beginning their artistic careers.” And in the 1970s, cartoonist Trina Robbins and her peers started a publication called Wimmen's Comix because “their male counterparts in the underground comix movement in the San Francisco area were not open to including their work in anthologies.”

“Brenda Starr, Reporter” carried on her adventures in papers until 2011, but Messick retired in 1982, after four decades of drawing her comic. “She brought on other female cartoonists to continue the feature—that’s what she wanted,” explains Kennedy. Over the character’s 70-year-run, the comic strip was only ever drawn and written by women.

"Drawn to Purpose: American Women Illustrators and Cartoonists" is on view until October 20, 2018, with its companion book, published by the University Press of Mississippi in association with the Library of Congress, due out in March. The show’s second rotation goes up on May 12.